Timing of ADT and Chemotherapy

How to cite: Keane, Thomas E. “Timing of ADT and Chemotherapy” January 27, 2018. Accessed. [date today] https://grandroundsinurology.com/Timing-of-ADT-and-Chemotherapy/

Summary:

Thomas E. Keane, MD, discusses how the current prostate cancer treatment paradigm is evolving. He argues for moving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) upfront in a patient’s treatment, but also acknowledges this approach could potentially hinder responsiveness to second-line therapies.

Reveal the Answer to Audience Response Question #1

- A. True

- B. False

(Twitter Question) Reveal the Answer to Audience Response Question #2

- A. True

- B. False

Reveal the Answer to Audience Response Question #3

- A. True

- B. False

Timing of ADT and Chemotherapy – Transcript

Click on slide to expand

Androgen Deprivation therapy (ADT)

ADT therapy largely with LHRH agonists is currently the standard of care in the management of newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients. Whether you combine it with an anti-androgen or not, it induces PSA responses, but inevitably, castration resistant disease appears at an average of 18 to 24 months.

Chemotherapy in castration resistant prostate cancer

Chemotherapy is typically considered as a last resort, or was up until recently, when there were a number of trials which suggested that it played a role earlier in the disease.

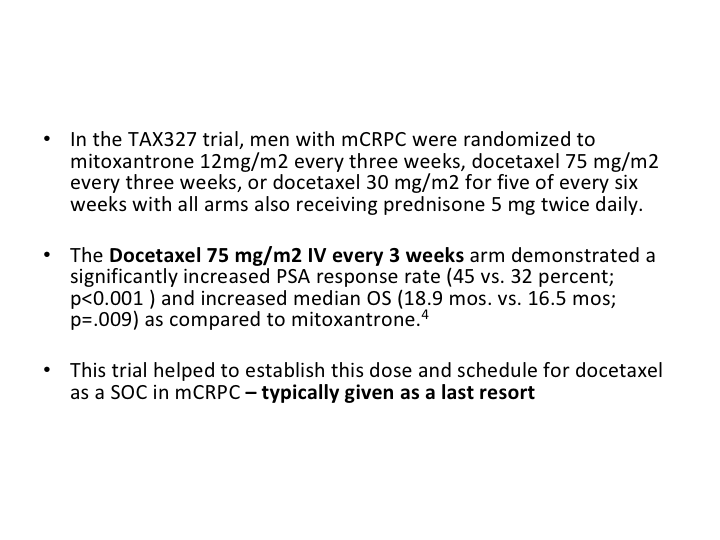

TAX327

The use of chemotherapy in prostate cancer really came from two studies. One was the SWOG study. The second was the TX327 study. The SWOG study identified the fact that we didn’t need estramustine, but both of them showed the docetaxel given at a dose of 75 mg/meter squared every three weeks was the most effective treatment, but typically up until recently, it’s been a last resort.

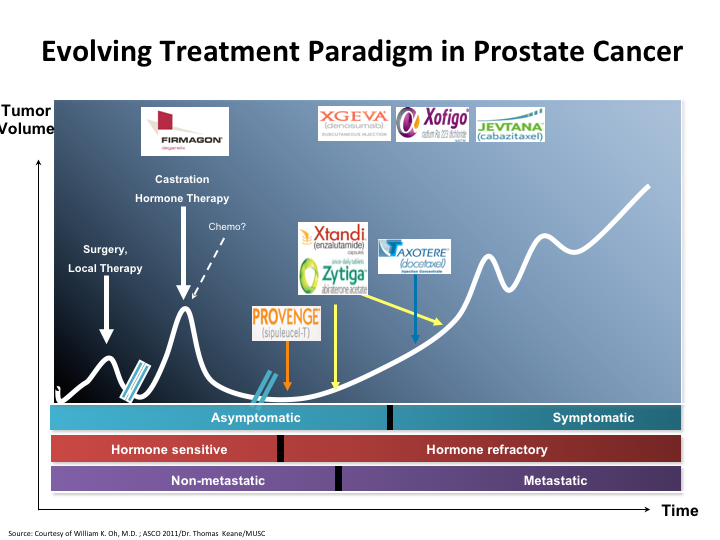

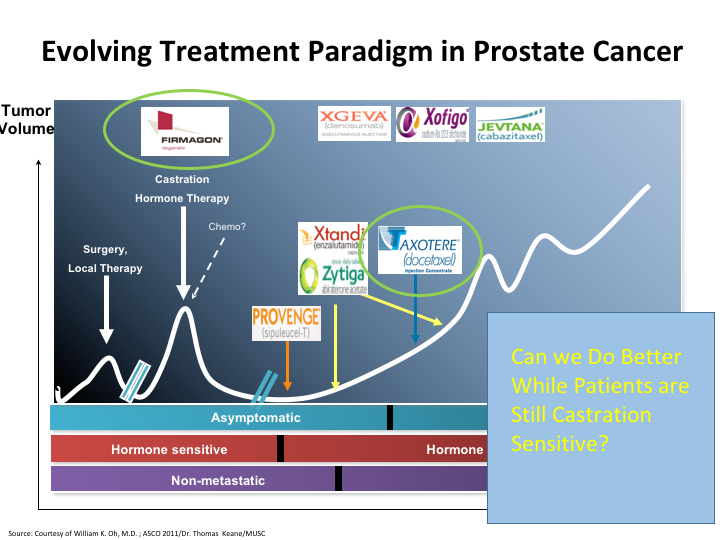

Evolving Treatment Paradigm in Prostate Cancer

If we look at this slide, it’s basically the evolving treatment paradigm in prostate cancer. You see that there’s been a major change since 2004 when docetaxel was first put on as a viable treatment, and all of these other things came behind.

Change Ahead

The fact is though it’s been changing and changing rapidly over the last three to four years, and it’s wonderful to see it. I think the whole face of treating prostate cancer is changing very quickly.

Evolving Treatment Paradigm in Prostate Cancer

The question still remains, can we do better while patients are still castration sensitive? Because, that is the area that I think the disease is more susceptible to the therapies that we give. And here you see once again a list of the therapies, and if you look here, chemo has been moved up on that list. There’s other changes that have occurred. We’ve heard about the antagonist versus the agonist, and we’ve also seen that Taxotere has now been moved to the castrate-sensitive state, and there may be more moves afoot.

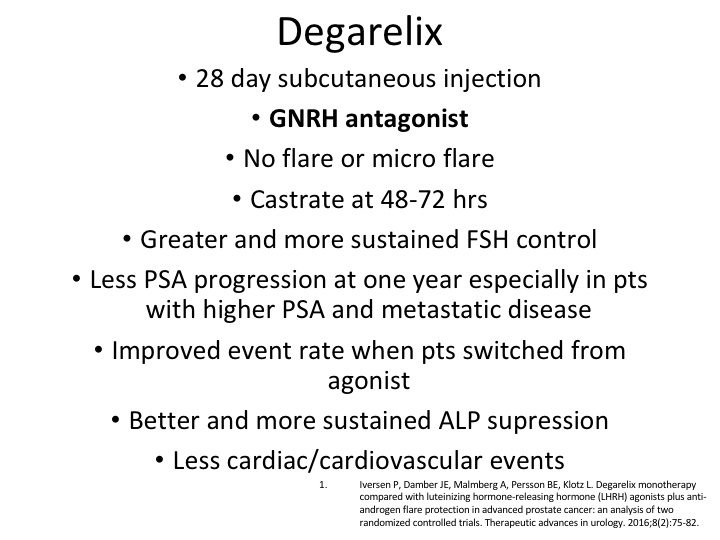

Degarelix Monotherapy

I’m not going to go through this again, but the degarelix monotherapy there was actually a very good paper by Peter Iversen, which was published in 2016, which was of two randomized, controlled trials of docetaxel. It was basically the original CS21, and then also the trial that was done with the three-month docetaxel, which as I mentioned before was only 89% effective, but therefore didn’t get approved. But there was a lot of patients that we could look at.

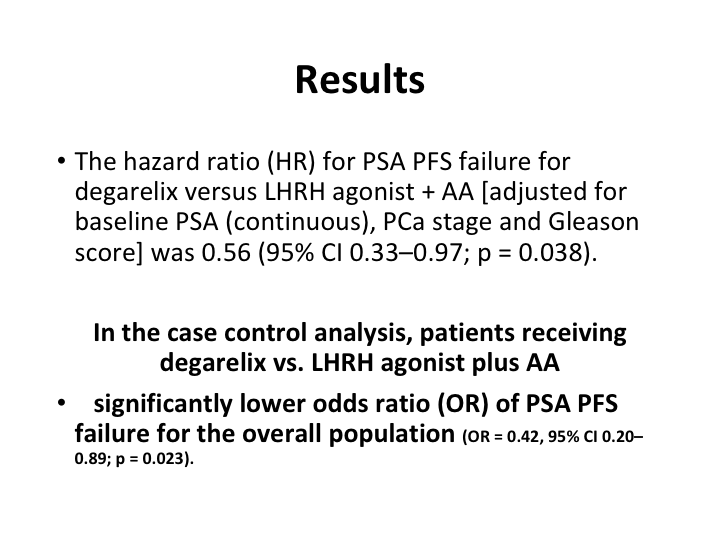

Data from 1455 patients

So the data from 1455 patients pooled from these two trials, evaluated degarelix versus an LHRH antagonist, and you can see that PSA progression-free survival was calculated and compared and baseline characteristics did differ somewhat between the groups, but there was a case-controlled analysis with a conditional logistic regression analysis.

Results

And what it showed was in the case controlled analysis patients receiving the degarelix versus the LHRH agonist plus the anti-androgen did better, the patients on the deg.

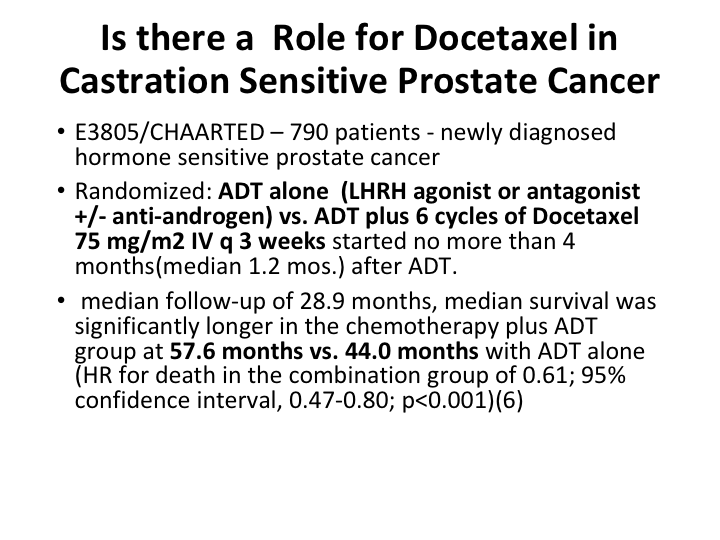

Is there a Role for Docetaxel in Castration Sensitive Prostate Cancer

So the question now becomes is there a role for docetaxel in the castrate-sensitive prostate cancer patient? And we have two excellent trials, one was CHAARTED and the other was STAMPEDE and basically CHAARTED had 790 patients. We all know the data.

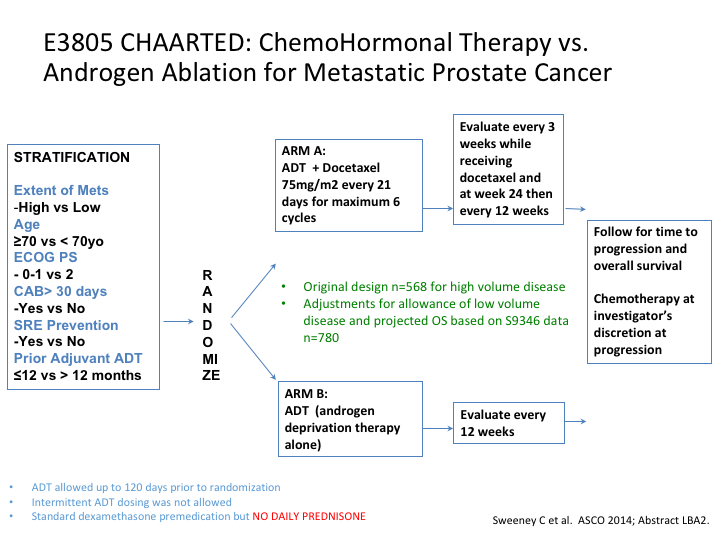

E3805 CHAARTED: ChemoHormonal Therapy vs. Androgen Ablation for Metastatic Prostate Cancer

If we look at it, it was stratified for both low and high-risk patients, and when the results came in, they started off originally with 568 patients but it rapidly increased to 780 to include more low-risk patients.

E83805 CHAARTED: ChemoHormonal Therapy vs. Androgen Ablation for Metastatic Prostate Cancer

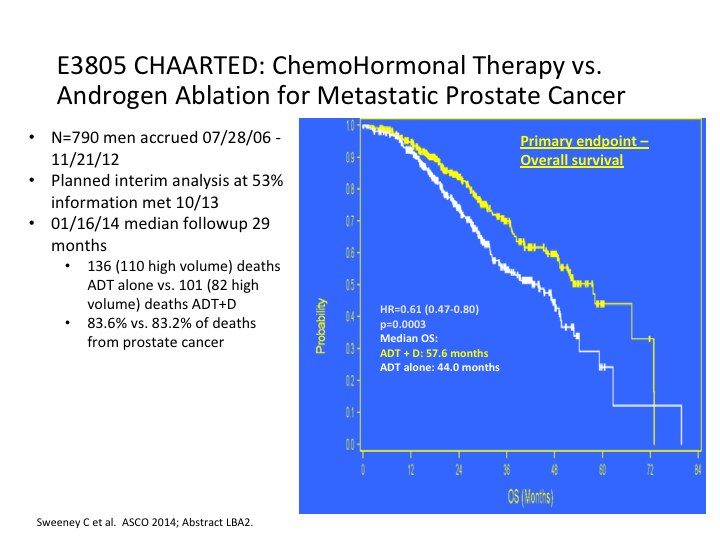

What they found was there was a substantial nearly 14-month difference in the trial overall, for overall survival. That is going with everybody.

E3805 CHAARTED: ChemoHormonal Therapy vs. Androgen Ablation for Metastatic Prostate Cancer

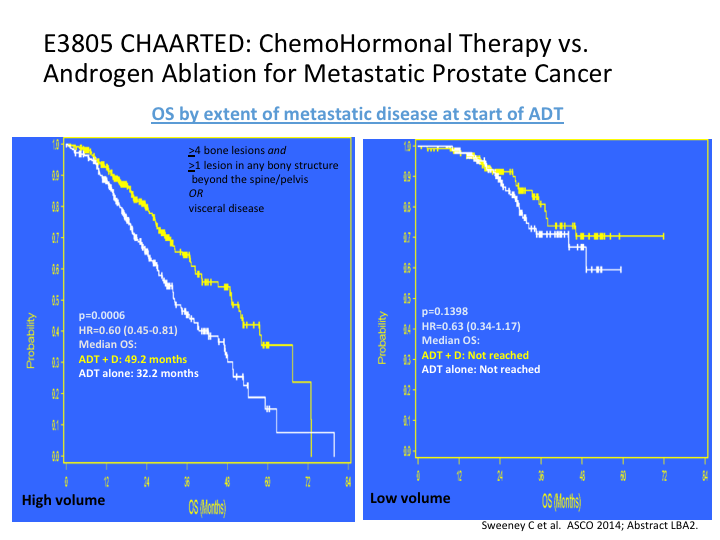

Most of this benefit was seen in the high-risk patients versus the low-risk patients. That was the first sign that we had that created quite a stir. Everybody was suddenly, man, we need to go with chemotherapy earlier.

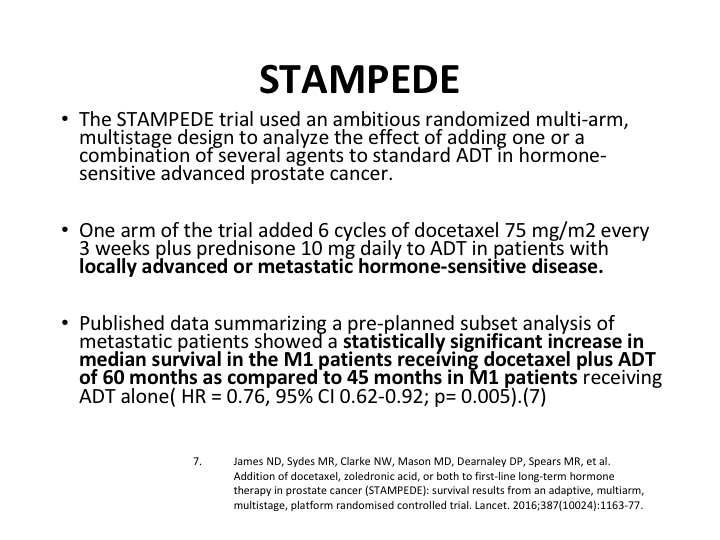

STAMPEDE

Now, there was some concern because there was a second trial, the GETUG-15 trial, which I will mention in a second, but these findings were confirmed by the STAMPEDE trial STAMPEDE is a unique trial. It’s a very ambitious randomized, multi-arm, multi-stage design to analyze a variety of different therapeutic interventions, and the control group remains the same for each of the interventions because it’s being done simultaneously if you like. There’s the same control group. Basically, what it showed was again the use of chemotherapy in the castrate sensitive patients was effective. Now, they had some patients who were not even metastatic disease at this point. So the published data summarized a pre-planning subset analysis of metastatic patients which showed a statistically significant increase in median survival of the M1 patients who were on the chemo plus ADT. And it was 60 months versus 45 months.

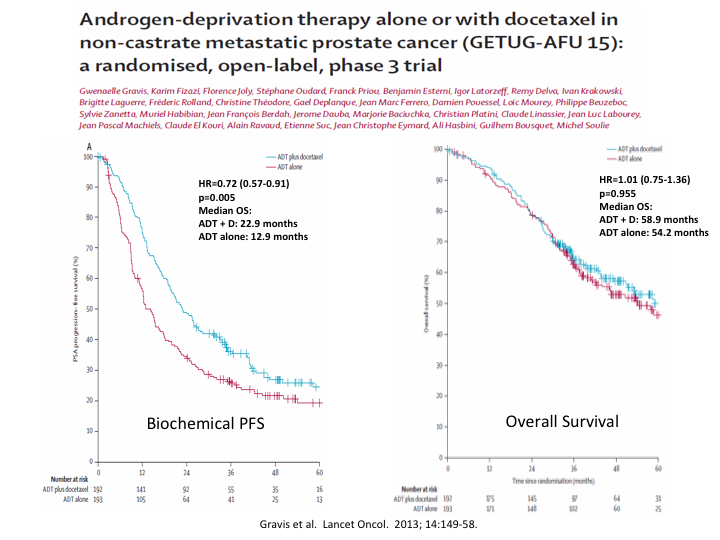

Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): A randomized, open-label Phase 3

I mentioned the GETUG trial from France, which was published around the same time, and which while it did show a difference in biochemical progression-free survival, it showed no overall survival.

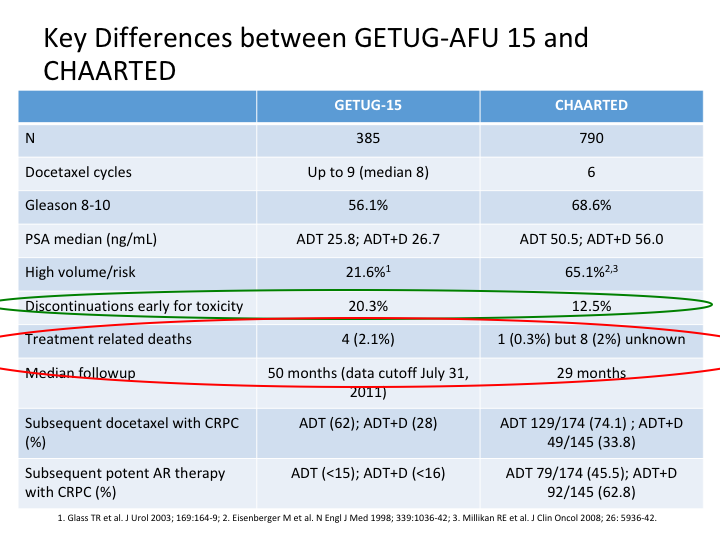

Key Differences between GETUG-AFU 15 and CHAARTED

And this slide is Evan’s and he gave it to me, but basically he looked at CHAARTED versus the GETUG-15, and as you can see there’s a number of differences, which immediately become apparent. Discontinuation for early toxicity was considerably more in GETUG. There were different numbers of patients, 385 in the GETUG versus 790 in the CHAARTED. Docetaxel cycles roughly the same, slightly more in GETUG. Gleason 8, yeah reasonable in both, but more in CHAARTED. PSA median was different, and treatment-related deaths were almost back to the TAX327 in the GETUG, slightly different in the CHAARTED.

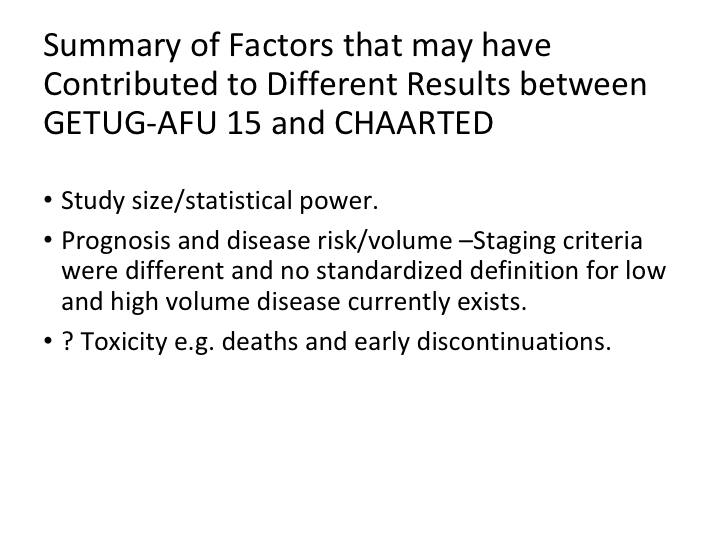

Summary of Factors that may have Contributed to Different Results between GETUG-AFU 15 and CHAARTED

So after we looked at this, we went back and found there is a study size and statistical power difference. There’s prognosis, and disease risk volume differences, staging criteria were different, and there was no standardized definition for low versus high-volume metastatic disease, and I’ve been talking about that for the last year, but we really do need to somehow standardize what we call low risk, and what we call high-risk metastatic disease. And the toxicity was different between the two of them.

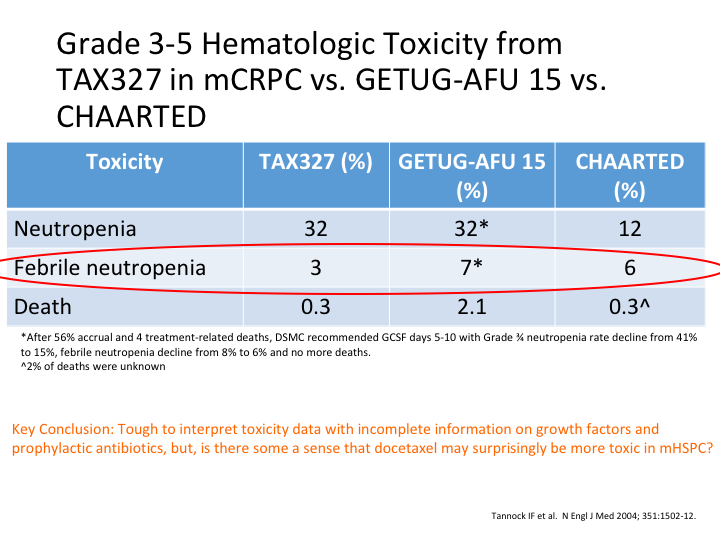

Grade 3-5 Hematologic Toxicity from TAX327 in mCRPC vs. GETUG-AFU 15 vs. CHAARTED

If you look at TAX327, GETUG-15 and CHAARTED, you can see here neutropenia was almost the same in the GETUG study as—it was the same as the TAX327. Febrile neutropenia, again there was a lot in the GETUG-15, and deaths there was a lot in the GETUG-15. Why was it? Key conclusion, it’s tough to interpret this toxicity data with incomplete information on growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics, but there is some sense that docetaxel may surprisingly be more toxic in the hormone sensitive metastatic patients.

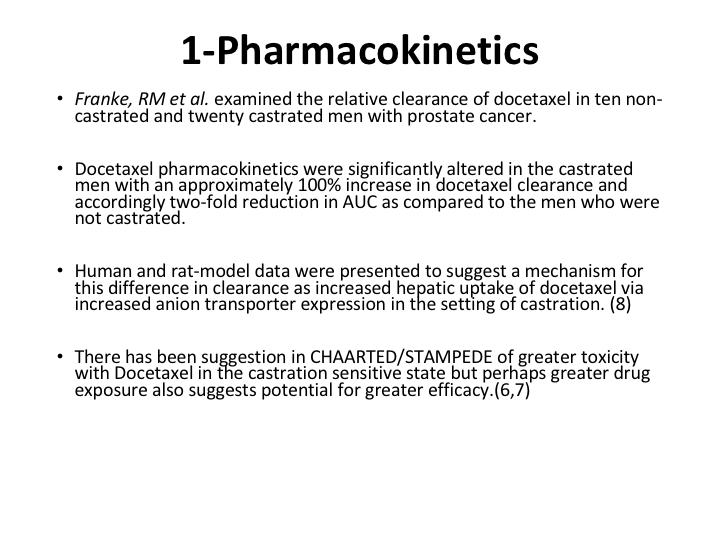

Pharmacokinetics

Now, why is that? Well, it’s not a surprise at all because Franke et al examined the relative clearance of docetaxel in 10 non-castrated and 20 castrated men with prostate cancer. Docetaxel pharmacokinetics are significantly altered in the castrated men with an approximately 100% increase in docetaxel clearance and accordingly a two-fold reduction in the area under the curve as compared to men who are non-castrate. To put it bluntly, the liver kicks it out if you are castrate. If you are not castrate, far more of the docetaxel gets in.

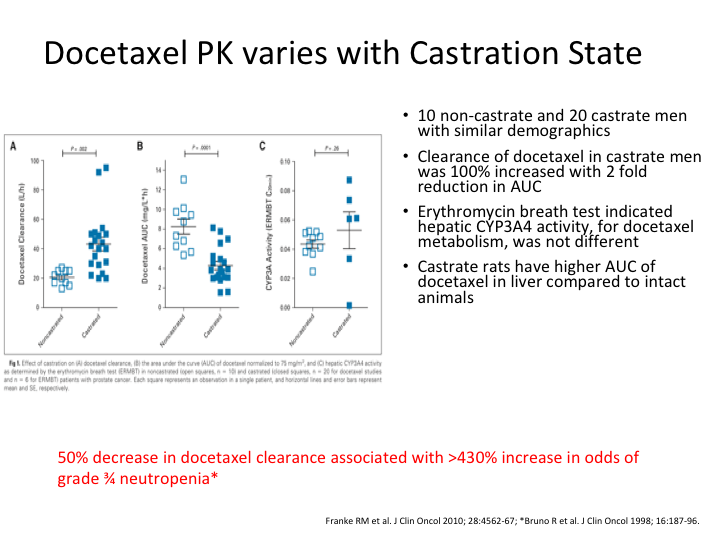

Docetaxel PKP varies with Castration State

Hence you are likely, and this is basically one of the graphs from that, you are far more likely to see toxicity if you are still castrate sensitive, and a 50% decrease in docetaxel clearance was associated with an over 430% increase in the risk of grade 3 to 4 neutropenia. So there we are sitting in the pub and now we’ve had probably three or four pints, and we looked at each other, and we said, damn, if the toxicity is greater, might not the efficacy also be?

But What About Docetaxel Before Medical Castration

And when we went back and looked, we found that a significant number of patients in the GETUG study were given their chemotherapy two to three weeks after getting their LHRH agonist. They weren’t castrate. So the rationale? What about giving docetaxel before medical castration? How about we take a look at it and see? What’s the rationale for that?

1. 2. 3.

What’s the rationale for that? There’s three areas you look at, pharmacokinetics, in vitro/in vivo data, and human data.

2-Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

So if we look at the prostate cancer cell lines that showed increase sensitivity to taxane-mediated cell death in response to androgen stimulation of the androgen receptor. In one series, androgen-dependent LNCaP prostate cancer cells showed a decreased survival when cultured with steroid hormones and paclitaxel as compared to cells depleted of steroid hormones. The mechanism is supposed to be caspase-dependent apoptosis in the presence of p53 activation and cellular proliferation.

LNCaP-bearing Mice

If we look at LNCaP-bearing severe combined immunodeficient mice, tumor volume and tumor apoptosis were measured in response to castration alone, docetaxel alone, both interventions administered concurrently, and both interventions administered in different sequences. Docetaxel administered prior to castration yielded the longest delay in tumor growth and studied interventions.

Pre-clinical data

If they were on tamoxifen, they did not do as well as if they got the docetaxel before they got their tamoxifen.

4-Human Trials

What about human trials in prostate cancer? Hussain et al treated 39 men with non-castrate level testosterone and increasing PSA post definitive therapy for localized prostate cancer. That was a radiation with up to six cycles of docetaxel at the dose I’ve already mentioned. Chemotherapy was followed by androgen blockade. Serum PSA decreased over 50% in almost 50% of the men on the docetaxel alone, and 75% in 20% of the patients on docetaxel alone. Only one patient had increased PSA at the end of the docetaxel therapy.

Hussain et al. continued…

The majority of patients had PSA progression after stopping their ADT but interestingly five of the 33 patients had an undetectable PSA at a median of 18.9 months after stopping ADT. 7 of the men in this study had radiographic evidence of metastatic disease and 3 of those were among the long-term survivors.

Our Proposal

So that has led to a proposal where we’ve actually gotten a trial funded which looks at a Phase 2 study of docetaxel before medical castration with degarelix in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer. The theory behind it is we’ve given the four cycles up front. They will need protection. They will need antibiotics. They will need to be assessed for toxicity. We treat them as necessary with GmCSF, and then they get castrated. And we want something that is going to castrate them quickly, ergo we give them docetaxel, and then they get the last two. We’ve now accrued almost-we have 15 patients to date. It’s a phase 2 so we’re trying to get 50 patients.

So in answer to the question timing of ADT, why would you give ADT at the very end when the patient is at their most sickest? They can’t tolerate the dose, so if you’re going to give it, we know today we should probably give it at the time that you’re going to do ADT. That makes sense, when they are still castrate sensitive. But let’s move it even forward. And make then non-castrate. That is the trial that has to be done, because I now having looked at it, that is something I really want to know because if you can get more in, if they are healthier patients, you may see a benefit. We certainly have the evidence pre-clinically and some early clinical evidence.

So I’m not sure what the timing of ADT should be, but I certainly know it probably shouldn’t be at the very end of life, and the other question I have is if we are going to start using all of the androgen ablative therapies, okay, let’s do that. But if we do it be prepared for early resistance. We all know that if you give abiraterone, and the patient breaks through it, enzalutamide isn’t going to be as responsive because of the ARB7. And visa versa. You can give whichever you give first, the second one doesn’t work as well. However, we do know they remain sensitive to taxanes. So perhaps it makes sense that if you did fail one of these novel therapies you should use your chemo there, and then there is evidence that you may get a reversal of some of the AVR7 and then there will be—there’s a couple of small studies that came out of Hopkins, I think showing that at that stage you can reintroduce the other novel therapy.

So that’s all I have. We don’t know the answer, but I do feel that it is probably earlier rather than later. Thanks very much.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Thomas E. Keane, MD, is Professor and Chairman of the Department of Urology at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Dr. Keane specializes in managing prostate, bladder, and renal cancers.

An avid researcher, Dr. Keane has served as principal investigator or co-investigator on more than 20 major clinical and preclinical studies. Much of his work focuses on innovative concepts in translational research, including utilizing human tumor xenografts to investigate the efficacy of new therapies as they relate to GU malignancies with particular reference to cytotoxic agents, sphingolipids, and boron-containing compounds. He holds a United States patent for sphingolipid derivatives and their use.

Dr. Keane’s research has led to publication of more than 100 articles peer-reviewed in such journals as The Journal of Urology, Urologic Oncology, and the Journal of Vascular Surgery. He provides editorial services to publications ranging from Urology to the International Journal of Cancer and is co-editor of the text Glenn’s Urologic Surgery, 6th, 7th, and 8th Editions. He is an accomplished speaker, having delivered many presentations to professional societies and symposia throughout the United States and abroad.